From the runways of high fashion to the remote rainforests of the Amazon, photographer Owen Deutsch has always had an eye for beauty. These days, his lens is more likely to be fixed on the avian subjects. Passionate about bird photography and conservation, Owen has spent the past two decades capturing the dazzling diversity of birdlife around the globe.

Now, with a brand-new book set to release this July, he invites us to see the world as he does: full of colour and wonder. DIYP caught up with Owen to find out more about his work and the lessons birds (and fashion) have taught him.

DIYP: Can you tell us a little about how you got started in photography and your background?

Owen: I got started in photography at the age of 11, when a friend invited me into the darkroom of a local community center. It was magic, literally watching the pictures come up in the developer. I was hooked from that very first day. My dad then helped me build a very rudimentary darkroom in the basement of our home. Then I started developing pictures for friends and charging them for it.

With the money I had saved, I bought a Yashica twin lens reflex. After another year of learning photography, I got good enough that I approached a local sports attire store that outfitted the clubs at my high school with jackets and struck up a deal to photograph the clubs wearing those jackets. These photos were on display at the store and available to purchase for all the club members. This job allowed me to upgrade my camera and darkroom equipment.

After college, I got a job at a commercial photography studio in downtown Chicago as a darkroom tech. Simultaneously, I went to night school at the Institute of Design for two years, studying design and photography. After two years, I applied to work for fashion photographer Victor Skrebneski as his assistant after seeing his work in a magazine and becoming enamored. I talked to his secretary and scheduled a meeting with him, in which I excitedly brought my portfolio to the meeting.

Upon opening my portfolio, Victor became confused, exclaiming, “You’re not a model!” Clearing up the confusion, I stated I was looking for a job as your assistant, to which Victor became relieved. We discussed my experience in running a darkroom, with special interest in running a color line (c41). This delighted Victor because he wouldn’t need to train someone, and the rest is history. We worked together for four years. I planned to always go into business for myself, which I did.

DIYP: How did your experience in fashion influence your approach to capturing birds?

Owen: A combination of beauty, design, and composition. Capturing beautiful fashion has helped me find the beauty in everyday life, and I apply this to the beautiful birds I photograph.

DIYP: Which species has been your favorite to photograph? And the most challenging?

Owen: There are too many birds to pinpoint my favorite species. My favorite bird is the one that lands in front of my lens. The most challenging are the ones that skulk. It took me about 18 years to finally capture a good photograph of a Riverside Wren, which was made possible during a trip to Costa Rica in late 2024.

DIYP: You emphasize the importance of backgrounds and lighting in your bird photographs. Can you share your process for selecting locations and times of day to achieve the desired look?

Owen: First and foremost, I go where the birds are. I almost always have a guide to help me be in the right place at the right time to photograph the birds. Their knowledge is invaluable to me.

My favorite backgrounds include blossoms and flowers, which are most prevalent in the springtime. As far as times of day, I have learned over the years that the best times are early morning and sunset, when the light is low, less contrasty, and the prettiest. It’s also when the birds are the most active. If I’m out shooting midday when the sun is high, I try to shoot under the canopy of the forest where you can find beautiful shadows and light.

DIYP: What camera and lens setup do you usually use? And what gear would you recommend for someone just starting bird photography?

Owen: I currently use two Nikon Z9 bodies, with an 800mm f/6.3 lens on one body, and a 100-400mm 5/4.5-5.6 lens on the other. I also have a 500mm f/5.6E PF lens that I’ve kept from my days using DSLR’s as the bokeh is fabulous.

Mirrorless cameras have replaced DSLR’s. I rarely use a tripod nowadays because mirrorless technology has advanced so much, with amazing image stabilisation for one, I feel confident in hand holding for all of my work. The advantage of hand holding a camera allows you to move around quickly and reposition yourself, getting the optimum view of the bird with beautiful backgrounds. You can get down on the ground, emulating the point of view of the birds themselves.

For someone just starting out in bird photography, I recommend getting the best gear you can afford. One brand isn’t going to be superior to the other, you will always be able to make do with what is within your budget. That being said, it would be best to purchase a camera with a high frame rate. This will help you capture birds in motion. Also, acquiring a long zoom lens will give you the best bang for your buck. Something around 150-600mm will cover all your bases.

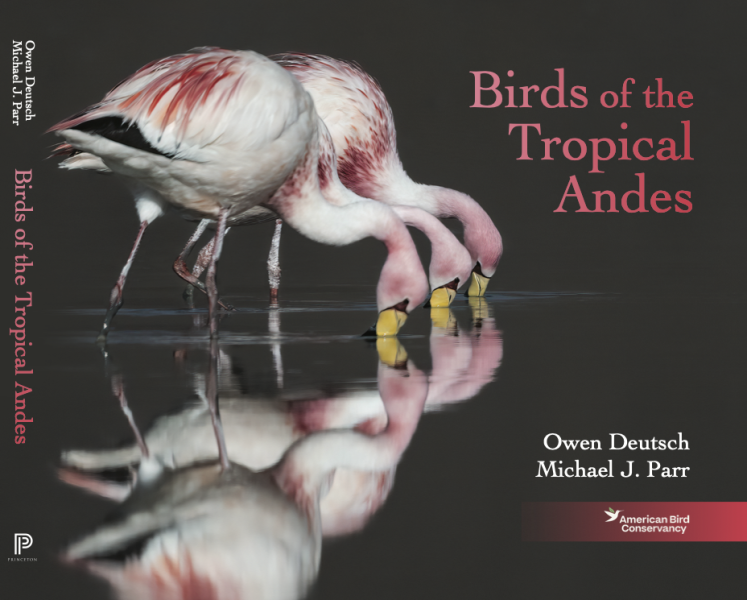

DIYP: In your book Birds of the Tropical Andes, you showcase the region’s avian diversity. What were some of the unique challenges and rewards of photographing in such a biodiverse yet rugged environment? Do you have any moments that really stood out that you can tell us about?

Owen: Shooting at elevations from 10,000-17,000 feet can wreak havoc on the body and head, so in planning the trips, we would gradually acclimate to the elevation from 4,000-17,000 feet over 3 or 4 days. I also took altitude pills.

We would usually have to get up between 4am and 5am so we could drive to where we planned to shoot so we could get in position so the birds wouldn’t see us moving around. This was especially true when photographing the Red-fronted Macaws, who are very sensitive to movement and noise. We had to be motionless, laying on the ground, otherwise the flocks would immediately vacate their location.

On our second day of shooting, our Colombian guide came down with COVID-19, so we knew we had to immediately get out of Bolivia. We made a mad dash for the airport without having any reservations. This drive took about 5 hours. We had to do this before we also came down with COVID-19, otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to leave the country. We got lucky and were able to get on the internet in the car and managed to book a flight back home before any of us got sick. After we got back to the States, all three of us eventually succumbed to the sickness and tested positive for COVID-19.

Two weeks after we all tested negative for COVID and were healthy, we returned to South America so we could finish the originally planned expedition. This trip went according to plan, and we all stayed healthy.

DIYP: Your work often highlights the importance of bird conservation. How do you balance the artistic aspects of photography with the goal of raising awareness about environmental issues?

Owen: I believe they are one and the same. I feel it’s the artistic aspects that engage the viewers to develop a love for these gorgeous creatures, to want to save them from disappearing so future generations can appreciate them too.

DIYP: What advice would you give to photographers who are passionate about wildlife but are just starting out in bird photography?

Owen: Just do it! Get involved with people who have similar passions, whether it’s an association like ABA and their Young Birders program, Audubon, or a bird club.

DIYP: Over the years, how has your perspective on photography evolved, especially in the context of technological advancements and changing environmental landscapes?

Owen: Technology has always been a challenge for me. I was never one to jump from one brand to another. I have been a Nikon shooter all my life. Of course, there are other great brands, but every time one manufacturer comes out with new technology, the others aren’t far behind. They sort of leapfrog from each other.

Changing environmental landscapes is a continuing problem, which is why I’m a supporter of the American Bird Conservancy. It is their mission to save the habitats that all these birds need to survive.

DIYP: Are there any upcoming projects or locations you’re excited to explore in the future that you can tell us about?

Owen: As I write this, I am packing for my next trip to Colorado and Nebraska, where I will photograph Sharp-tailed Grouse, Greater Sage-grouse, Greater Prairie-chickens, Lesser Prairie-chickens, and other prairie birds such as Longspurs. I’m also planning an expedition to Brazil early this summer, as well as Botswana at the end of the year.

I’m in the early stages of developing a potential third book. I also aspire to create a children’s book, which would help instil a love for birds and conservation at a young age.

Owen’s new book, Birds of the Tropical Andes is available to pre-order here.